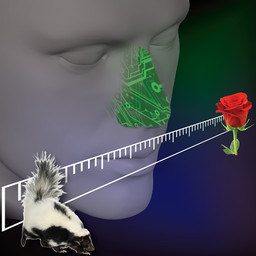

Writers love their work, or they wouldn’t be writers. The problem is that writers also tend to love their characters and plot devices, even when those things don’t stand up to close (sometimes even casual) scrutiny. Reviewing a manuscript provides with the invaluable opportunity to put every aspect of your work to the sniff test, using common sense to check the believability of a plot device or a character’s behavior.

Writers love their work, or they wouldn’t be writers. The problem is that writers also tend to love their characters and plot devices, even when those things don’t stand up to close (sometimes even casual) scrutiny. Reviewing a manuscript provides with the invaluable opportunity to put every aspect of your work to the sniff test, using common sense to check the believability of a plot device or a character’s behavior.

Believability is really the key to this test. A common horror movie trope has the victims exploring the boarded up house in the middle of the night, even though they are fully aware there is a killer loose and their flashlight has just run out of batteries. This seems so unlikely as to be ludicrous in any story that attempts to take itself seriously. While it’s true that panicked people can and consistently do make exceptionally foolish choices, this one just isn’t within the range of possibilities. It’s not believable. It doesn’t pass the sniff test.

Does that mean that every character needs to make the best possible choice in every scenario? No; that also fails the sniff test. The reader isn’t actually looking for every choice and every situation to fit the best-plan scenario. The reader actually wants things to follow naturally, or at least to seem like they’re going to follow naturally. The reader wants to believe that this story could unfold in this way, and that these characters will behave in this manner. This benefits the writer in that the reader will tend to be forgiving of small missteps, but it also means the reader is critically judging the story probably far more closely than the writer.

When reviewing a manuscript, the writer must develop the ability to set aside his knowledge of future developments and test each portion of the story as it unfolds. If a portion of the story fails to pass muster, the writer has the opportunity to slap some red ink on the page and fix the problem. The critical test in this case is that any given action must follow logically from the immediate context of the problem, without reference to additional information from other stories or later portions of the manuscript.

One of the key factors at play is the tendency of any given story to be any given reader’s first exposure to this set of characters or situations. This is especially important in series fiction, where characters and settings carry continuity from one story to another; while this can create a larger setting and deeper characterization, it can also leave the reader requiring excessive amounts of additional information in order to enjoy the immediate story. There is a temptation to “data dump” information on the reader so that he is correctly informed, a solution that does not constitute good form in storytelling. In this instance, a better solution would be either trickle the information to the reader in the paragraphs leading to the incident, or rework the context of the situation so that less specific knowledge is required.

Perhaps most often, the sniff test fails when a writer has decided to frame a particular scene, and requires events to unfold in a certain way. Because these scenes are beloved, they may be difficult for the writer to identify during a review; there are a few simple questions that can help identify them. Is this the only possible outcome? Is there a simpler outcome? Is there an outcome that will better suit the characters? Is there an outcome that will better suit the story? If the answer to any of these is “yes”, then the writer needs to rethink and rework the scene in question.

More often, the sniff test fails in the instigation of a scene rather than its execution. In this case, the writer needs to examine the initial incident and ask: Is it possible? Is it probable? Is it plausible? Is it likely? If the answer to any of these is “no”, the scene has a serious problem.

The reader is going to be far more critical of a story than the writer, almost inevitably. The writer’s job is to prevent that critical eye from tossing away the story in frustration at the lack of believability by providing the reader with characters and scenes they can understand and that logically follow each other. Reading already requires suspension of disbelief, the reader who smells something funny in the plot will not have a good experience.

Last 5 posts by Winston Crutchfield

- Disney Kingdoms comics - July 7th, 2017

- Sonic the Hedgehog - June 19th, 2017

- He-Man / ThunderCats - June 5th, 2017

- Scooby Apocalypse - May 15th, 2017

- Wacky Raceland - May 1st, 2017

How about a heroine/aspiring victim in such a movie, on foot, being pursued by a psycho serial killer in a car, in the middle of a heavily forested area with about a million potential hiding places, so she runs straight down the middle of the road?

I love that phrase, “aspiring victim”. Maybe there’s good reason to run down the middle of the road. Maybe the forest is populated by ROUS (though I don’t believe they exist). As long as there’s a good reason, the middle of the road is the best place to run! 🙂